On March 17, 2015 - appropriately enough, at the close of a very active period of late winter weather in the Northeast - a strong solar storm created outstanding aurora displays worldwide. The storm was classified as a 'G4,' meaning it had the potential to be visible as far south as the mid-Atlantic states. Though the storm peaked during daylight hours in the Northeast, it remained active after dark. This image was taken at Harvard Pond in the north-central Massachusetts town of Petersham. Many other images from around the country showed a distinct green glow, appropriate for St. Patrick's Day. The purplish pillars were similar to ones I saw in New Hampshire in September 2014, a display that was also visible in Massachusetts. The March 2015 aurora was also visible on Cape Cod and other points south.

Aurora displays (known as Aurora borealis in the north and Aurora australius in the southern hemisphere) are formed by interactions between particles from the sun and Earth's atmosphere. They most often are green or pink, but other hues may be visible depending on the types of gases.

Though viewing the northern lights outside of the highest latitudes often involves lots of patience and a dose of luck, there are many resources currently available that increase your odds. Websites such as http://www.spaceweather.com and NOAA offer forecasts that can give as much as several days advance notice of a storm. Once a storm is in progress, check pages such as http://www.softservenews.com/Aurora.htm or Facebook sites for short-term updates. You can even sign up for customized aurora alerts to your phone. One of the key items to track is the 'kp' index. In short, this number reflects viewing zones from north to south. The higher the number, the further south the aurora will likely be visible. The locale in the image is right on the kp 7 line, and when the storm spiked to an 8 shortly after 10:00 PM, the aurora became visible.

When choosing a viewing area, a clear view of or near the northern horizon is an obvious necessity, and the further away from light pollution the better. A bright moon may make it difficult to see faint auroras. If you can get to or live near a landmark such as a lighthouse, barn, mountain, or the like, it will add a point of interest (as long as it doesn't obscure the view). If you get there before sunset, you'll be able to scout vantages and get your camera's focus set. Patience is an essential part of observing and photographing auroras - be prepared to wait extended periods of time for a show that might last just a few minutes.

Once you're in position and witnessing a display, basic photography essentials include a sturdy tripod, cable release or self timer, extra batteries (especially on cold-weather nights), and adjusting to the necessary ISO for the conditions. The intensity of the display and overall scene will affect exposure times. Be aware that your camera's display monitor will look brighter in the dark than the actual image that gets recorded. In post-processing, use tools such as luminosity and clarity to reduce noise and definite features. It's tempting to push saturation and vibrance to make the colors pop, but be careful about going too far and making the scene look unnatural. Keep an eye on the forecast and sky, and good luck!

The extended period of winter storms and Arctic cold during the mid-late winter of 2015 has resulted some unusual scenes around Cape Cod Bay as winter slowly recedes from the New England coast.

Large ice blocks in Wellfleet and Truro (above) have attracted national media attention.

The ice formations, seen here at Great Hollow Beach in Truro, were constantly changed by tides.

An overwintering common loon navigates the ice field off a Truro beach.

Sunset from Great Hollow Beach in Truro as the ice shifted north along the bay.

Overview from Truro looking towards Provincetown on March 11.

The recent return of great white sharks to Massachusetts coastal waters has been an interesting and highly publicized development. I've been gathering information related to shark sightings, gray seals, and related habitats such as Monomoy Island and the National Seashore ocean beaches. Here's a timeline of key events:

(Above: Gray seal colony off Lighthouse Beach near Chatham Harbor's inlet, a hotspot of shark activity).

1603: English explorer Martin Pring notes large seal population off Truro.

1865: Henry David Thoreau's Cape Cod includes references to great white sharks.

Late 19th century - 1962: Massachusetts enacts bounty on seals, which are hunted to near extinction in New England.

1936: A fatal attack on a swimmer off Mattapoisett is the last great white shark attack in Massachusetts until 2012.

1972: U.S. Marine Mammal Protection Act enacted.

1980s-1999: Gray seal population expands to roughly 6000 at Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge off Chatham.

1990: A single great white is seen off Cape Cod, the only sighting for 5 years.

2004 September: A great white is entrapped in a shallow lagoon on Naushon Island for several days.

2006: A Thanksgiving Day storm connects South Beach and Monomoy Island, disrupting seal travel and prey fish corridors; numbers subsequently decline at Monomoy and increase elsewhere. 500-600 individuals estimated near Chatham Fish Pier.

2008 June: Passengers on a Monomoy Island Excursions tour boat witness a shark attacking a gray seal.

July 11: Several sightings are reported at Edgartown, Martha's Vineyard, resulting in beach closures.

July 15: A dead small female great white washes up on the southwest shores of Nantucket Island.

2009: A large gray seal colony well-established at Head of the Meadow Beach in Truro, later shifts north to the High Head area.

2011 March: a single-day gray seal count indicates nearly 16,000 individuals in Massachusetts waters.

2012 July 9: a first-time sea kayaker is pursued by a shark off Nauset Beach, witnessed by many beach visitors.

July 30: A 50-year old man is bitten in ocean waters while swimming with his son roughly 500 feet off Ballston Beach in Truro. 50 stitches are required to close the wound, which is confirmed as a great white.

July-September: Ocean beaches in Chatham and Orleans repeatedly closed and reopened after sightings.

September 13: A giant 20-foot female is one of 6 great whites tagged off Chatham by Shark Hunters.

2014 August: The gray seal colony at High Head in Truro is an estimated 500-600 individuals.

August 25: A great white is spotted by police helicopter off Duxbury Beach, resulting in swimming closure; it lingers off the beach for more than an hour.

September 3: A great white overturns two female kayakers off White Horse Beach near Plymouth and bites one of the boats. The women are rescued without injury.

Recent visits to the Mass Audubon Wachusett Meadows and Cooks Canyon Wildlife Sanctuaries in central Massachusetts during the first week of July included the welcome sightings of a number of early summer monarch butterflies winging around the milkweed fields. Several friends and neighbors have also reported seeing them in their backyards and gardens. This is an encouraging development after the summer of 2013, when the monarch population crashed throughout the Northeast.

(Above: Monarch butterfly on milkweed)

Because monarchs are a well-known and highly visible species, their absence last year has generated a lot of attention. A combination of short and long-term factors was responsible for the 2013 decline. Record warmth and drought in 2012 slowed monarch reproductive activity, especially in the Midwest ‘Corn Belt,’ where a large percentage of the monarchs that overwinter in Mexico breed. This resulted in a record low number of monarchs overwintering in Mexico (only 3 acres of forest used, far below the average of 17 acres). This alone wouldn’t have resulted in the marked lack of sightings - they were fairly visible in 2012 after low numbers the previous winter. However, the spring of 2013 had more unusual weather, in this instance abnormally cool and wet conditions that adversely affected the northbound migration. Sightings were few and far between, and it was a poor breeding season. As a result, the 2013-14 overwintering numbers plummeted to an alarming low of just 1.7 acres.

(Above: Monarch on late summer goldenrod before winter migration)

Though 2013 was an unusual year, long-term monarch population trends are troubling. A significant concern has been the loss of milkweed, their sole host plant. Studies indicate that milkweed has declined by more than 20 percent over the past two decades, effectively eliminating nearly one-quarter of monarch breeding habitat. Milkweed is most common in Midwestern farmlands, where it was been reduced by recent agricultural practices, such as genetically modified crops that facilitate the removal of milkweed and other species that are regarded as unproductive weeds by farmers. The loss of former fields to forest regrowth and suburban development in recent decades is also a factor. In additional to its value to monarchs, milkweed is a key food source for many other butterflies and insects. Visit a milkweed patch now (mid-late July) and you'll often see masses of fritillary, tiger swallowtails, silver-spotted skippers, milkweed bugs, and other insects congregating around the blooms.

(Above: Silver fritillary (top) and tiger swallowtail on milkweed)

To briefly summarize the unique life history of monarchs, after 3-5 generations cycle through during the summer months, one long-lived generation undertakes the long migration to warm wintering grounds in Mexico and California in the late summer and autumn. In June, the next generations make the journey north to breeding grounds, and then the cycle begins again. Given the geographic spread, susceptibility to weather, and numerous other factors, conservation is a complex challenge. Though the long-term trends indicate recovery will be a long process, hopefully the early sightings of 2014 are a positive sign.

What a difference a few days makes…..at the last entry, spring was progressing sluggishly, and many early season wildflowers were still blooming. Over the past two weeks, the forests have rapidly greened up, and an entirely different group of species is rapidly cycling through. While there have been several unseasonably cool days this month and no prolonged warm spells, average temperatures have actually been a few degrees above normal for most of May in Massachusetts, and the season appears to have caught up. Here are some of the familiar mid-spring species in bloom:

Painted Trillium

Unlike slightly larger red trilliums which thrive in rich soils, these photogenic flowers favor acidic and boggy forest habitats. Their single flower's three white petals are centrally splotched with a maroon patch that attracts and guides pollinators to the flower. The leaves, also in threes, are dark green.

Pink Lady’s Slipper

A favorite of many wildflower enthusiasts, this orchid also thrives in acidic and boggy environments (it often grows under pines), along with rocky areas and deciduous forests with acidic, well-drained soils. It is named for its large pouch-like petal, which is shaped like a moccasin or slipper and blooms in hues ranging from magenta to pink to pinkish-white. Pink lady’s slippers often form colonies, though some grow individually. Like other orchids, the seeds interact with soil fungi to survive and reproduce. Bloom time is mid-May to June.

Columbine

This hardy flower grows in rocky woods, outcroppings, ledges, riverbanks, and woodland edges, sometimes in seemingly inhospitable places where there barely seems enough soil to support it, such as the rock cave shown below. The red and yellow flowers, which hang off a long stem, are favored by hummingbirds and butterflies. It blooms in mid-late spring.

Fringed Polygala

One of the most unusual wildflowers, fringed polygalas are distinguished by their tube-like true pedals, which are flanked by two petal-like ‘wings.’ They are sometimes mistaken for orchids. The leaves are dark green and similar to wintergreen. This is a low-growing flower, that reaches a maximum height of just 3-6 inches. It is a member of the overall milkwort family, the species of which are reputed to increase milk in nursing mammals.

Eastern Starflower

Logically named for the shape of both its flower and leaves, eastern starflower thrives in cool, moist woods and mountain slopes. Paired flowers have 5-9 pointed, star-like petals, and the elongated leaves form a similar pattern.

Bunchberry

Bunchberry is well-named, as it often forms dense patches in woods and bogs, including high mountain slopes, in May and June. White, petal-like ‘bracts’ surround the tiny green true central flower. Though related to high-growing dogwoods, bunchberries only reach 3-8 inches in height.

Bluebead Lily

Also known as Clintonia, this small lily has bell-like pale yellow flowers. It also favors cool acidic woods and mountain slopes. Bloom time is May to July; after flowering watch for (but don’t eat) the foul-tasting blue berries, which its common name is derived from. The long leaves are similar to those of pink lady's slippers and other orchids.

The next update will include the end-of-spring species, which include colorful favorites such as blue flag iris, and yellow and showy lady’s slippers.

As anyone who lives in the Northeast is well aware, a long, cold winter has been followed by a cool early spring, and the growing season is off to a very slow and patchy start. Nevertheless, the region's ephemeral wildflowers have been blooming nicely over the past couple weeks, offering welcome color to the leafless forests.

The spring ephemerals bloom in the mid-spring window between the last deep frosts and snowmelt and leafout on the trees. During this time, they take advantage of the light that reaches the forest floor through leafless woods. The various species each have distinctive flowering times and habitats. Knowing where and when to look is especially important with spring wildflowers, as the viewing season can be as short as a matter of days locally. You're not likely to find a colony of lady's slippers in mid-April, or bloodroot flowering in June. It's impossible to provide specific dates given New England's topographic and climactic diversity and highly variable spring temperatures, but below is a quick guide to some of the favorite early-season species.

Round-lobed Hepatica

The blooms of round-lobed hepatica, which can vary from purple to deep lavender blue to pale blue to nearly white, are a favorite of many naturalists and a welcome early sign of spring. The flowers close at night and on heavily overcast days to protect pollen stores. Flowering time is generally from mid-late April into early May. Areas with rich soils fed by limestone and marble are the best places to check for hepatica, which can be elusive to find even in suitable habitats.

Red Trillium

Also known as "purple trillium," "wake robin," or the rather unflattering "stinking Benjamim," this member of the lily family thrives in rich, moist woods. It blooms from late April to as late as late May or early June in highest elevations, such as the summit of Mount Greylock in western Massachusetts. Red trilliums often grow along streams and brooks, which can make for a nice photo opportunity. As its name suggests, each flower has three dark red/maroon leaves. Uncommon white or yellow variants may also be seen locally (below).

Bloodroot

This photogenic member of the poppy family features a white-petaled flower and a large leaf that grow on separate stems. The leaf initially envelopes and protects the flower bud. After emerging, the flowers, which have 7-12 petals, open in full sunlight and close at night. Habitats include floodplains, stream banks, talus slopes, and moist, rich woods. Dense colonies may also be seen growing in association with active abandoned garden sites. Blooming time in the Northeast is generally the last two weeks of April, though they may continue into early May in late years such as 2014.

Trout Lily

The bright yellow blooms of trout lilies can be found in moist hardwood forests, especially along river and stream banks, and in rocky areas such as cliffs, ledges, and balds. It is one of the first flowers to emerge in late April. It often, though not always grows in colonies or clusters.

Spring Beauty

These attractive flowers, with reddish or purple-lined petals, thrive in a variety of habitats in eastern deciduous forests, including rocky mountain slopes, bluffs, ravines, wetland edges, and even gardens and parks. Bloom time is late April and May.

The next installment will feature the next round of mid-spring species, including painted trillium, fringed polygala, and columbine.

New Hampshire's Mount Monadnock is well-known as one of the world's most-climbed mountains. Although its elevation is relatively modest at 3166 feet (roughly half the size of Mount Washington in the White Mountains), its isolation and barren summit give it the feel of a much larger eminence. And that's the reason for it's appeal - it offers the experience of a big mountain, accessible via relatively short trails that can be completed in a few hours.

Unlike the highest summits in New England such as the Presidential Range, Katahdin, and Mount Mansfield that have naturally open alpine zones, Monadnock's summit was cleared during the 19th century by a combination of human-set fires (possibly to eradicate wolves) and storms.

With an estimated 100,000 visitors annually, the popular Monadnock trails can be quite crowded at times, especially on warm-weather weekends. However, the reservation's 35-mile trail network offers a variety of options. Here are some highlights removed from the well-beaten paths.

Pumpelly Trail/East Ridge: At roughly 8 miles round-trip, the Pumpelly Trail is much longer than the other popular trails. However, while not to be underestimated the climbing is mostly easy to moderate, with just one or two short steep sections. What makes this route worthwhile are the numerous open viewpoints along the ridge. There are fine views across the countryside to the nearby Wapack Mountains, as well as Monadnock's summit, seen here from one of the junctions.

Bald Rock: You don't have to climb to the summit to enjoy great views. The mostly open shoulder known as Bald Rock on the south slopes offers a very interesting perspective, including long panoramic views and a good look at the summit above to the north. There are several options for reaching it. When I took this winter sunset, I followed the old Toll Road past the Halfway House, then took the Side Foot and Hedgehog paths to Bald Rock. The Toll Road and White Arrow Trails offer a fairly straightforward climb (an easy ascent on the road, then a steeper climb below the summit) from the parking area on Route 124.

Gilson Pond/Birchtoft Trail: Tucked at the base of the east slopes, Gilson Pond offers scenic views of Monadnock's looming profile and is also home to a state park campground. A pleasant and easy nature trail, excellent for families, circles the pond, with views of a beaver lodge and concrete dam. The Birchtoft Trail branches off the pond loop and offers a moderately difficult 3.5-mile route to the summit.

If you're interested in learning more about Monadnock and its rich history, Rabbit Ear Films is in the process of producing the first documentary of the mountain, Monadnock: The Mountain that Stands Alone. Check out their website for more infor: http://www.monadnockfilm.com/

The recent months have truly been the winter of the Snowy Owl. These Arctic visitors have been seen in unusually high numbers in many areas of North America, drawing countless bird watchers, naturalists, photographers, and families alike. Here in New England, sightings have been very common throughout much of the coastal region, and individuals have also been regularly reported inland in areas such as the Champlain and Connecticut River Valleys. At Boston's Logan Airport, as of late February a record number of more than 80 birds had been relocated to prevent collisions with airplanes (for context, the average winter sees just 6-8 relocations). Individuals have also made appearances in unusual places such as the summit of Wachusett Mountain in central Massachusetts, urban neighborhoods in the city of Springfield, and fields in mostly wooded hilltowns. On a broader scale, snowys have also turned up in unusual southern destinations such as Bermuda, the North Carolina Outer Banks, Florida, and Kansas.

Snowy owl populations and migrations are intricately linked with the population dynamics of small rodents called lemmings in their Arctic home region. When lemming numbers are high, snowy owls can be prolific breeders raising as many as a dozen hatchlings. However, when numbers are low, they may not even attempt to breed. Fluctuations in their prey along with weather result in periodic movements south during the winter months. Several similar movements have occurred in recent winters such as 2011-12, when snowys were also highly visible in New England and other areas (though not quite to the extent of this year). These migrations are known as 'irruptions,' or irregular seasonal movements of species that are dictated by food availability and other factors. Other species that have irruptions include winter finches such as crossbills and pine siskens, short eared owls, green darner dragonflies, and red admiral and painted lady butterflies (both of which were unusually common in the Northeast during the warm year of 2012).

During winter irruptions, snowy owls favor open areas that bear some resemblance to their Arctic tundra homes. These include coastal barrier beaches, airports, frozen tidal rivers and wetlands, and agricultural fields. They often perch atop places that allow them to survey the terrain for potential prey, such as dunes, fence posts, building roofs, telephone poles, barns, and even picnic tables (above)! Their prey includes small mammals and birds such as ducks. The farmlands of the Connecticut Valley in northwest Massachusetts, seen below from Mount Sugarloaf, are an example of an inland habitat where snowy owls have been reported this winter.

Salisbury Beach on the MA-NH border has been one of many reliable coastal locations. The owls frequent both the beach and dunes and the tidal marshes. Look carefully for the owl on the post right of center.

The female below (as indicated by dark markings, males are much whiter) was flying over dunes at Salisbury Beach.

Lunch grab for a patient hunter on the New Hampshire coast. After sighting this mouse and starting to fly from its perch, this owl held back at the last instant and waited several minutes for the perfect opportunity.

While it's easy to take sightings for granted during winters such as 2013-2014, by March the owls will again be northbound for their Arctic homes, and it's hard to predict when the next significant migration might occur (though nothing is certain, a repeat of this year would be unlikely). So if you have the opportunity in the next few weeks, keep your eye out for this possibly historic natural spectacle.

With more than 250 cascades, the Appalachian mountains and hills of western North Carolina are a waterfall lover's paradise. As a bonus, some of the state's largest and most distinctive waterfalls are easily accessed and viewed along the corridor of Route 64, a scenic highway (a 61-mile stretch is aptly known as the 'Mountain Waters Scenic Byway'). The following driving tour may completed in a full day or less, though you'll want to allow plenty of time to explore the area. While not especially dangerous, drivers should be prepared for tight curves as the highway snakes through the mountains.

The first stop is Looking Glass Falls which, though not as large or voluminous as some of the other waterfalls, is arguably the most picturesque. From the junction of Route 64 and 276 east of Brevard, follow 276 north for 5.9 miles to the entrance on the right. For those travelling on the Blue Ridge Parkway, Route 276 and the falls are easily accessed at milepost 412.2 just west of the Mount Pisgah area. A set of stairs offers a quick descent to a viewing area and the base of the falls.

After enjoying the falls (and other attractions of the Nantahala National Forest) backtrack to Route 64 and head west for roughly 32.5 miles to Cashiers. Turn south on Route 107 for 9.3 miles to the South Carolina state line, then left at a sign for Whitewater Falls and continue 2.3 miles to the junction with Route 130 (becomes Rt. 281 in North Carolina). At 411 feet, Whitewater Falls is the highest waterfall east of the Rockies. A paved, universally accessible trail leads to two viewing areas with long-distance views of the falls across the high valley. A medium-range telephoto lens is helpful here to zoom in on the cascades.

Return to Route 107 and head back to Cashiers. From the town center, you can continue north on Route 107 to a right on Norton Road, which leads 0.5 miles to Hurricane Falls. This 30-40 foot falls is visible from the roadside.

From Cashiers, continue west on Route 64 for 10 miles to Highlands. Here you will find popular Bridal Veil Falls, a true 'roadside attraction' in that part of the pulloff runs directly below the falls (below, a family poses beneath the cascades)! Use caution parking around here.

Just 0.9 miles further along is 75-foot high Dry Falls, which, in spite of its name and in contrast to nearby Bridal Veil Falls, often thunders with a high volume. One unusual characteristic of this falls is the trail that runs behind the cascade, allowing visitors an unique perspective.

The final stop on this tour is Cullasaja Falls. From Dry Falls, continue west on Route 64 for 5.5 miles to a viewing area at a pullout on the south side of the highway. Those stopping here should continue past the falls, then turn around and return in the eastbound lane to the pullout (use caution as the highway is quite narrow and windy here, and trucks and buses need the full width of the road).

Cullasaja Falls marks the western end of this tour, but there are many more attractions in the area worth exploring. From Franklin, several highways lead north towards the Smoky Mountains and Blue Ridge Parkway.

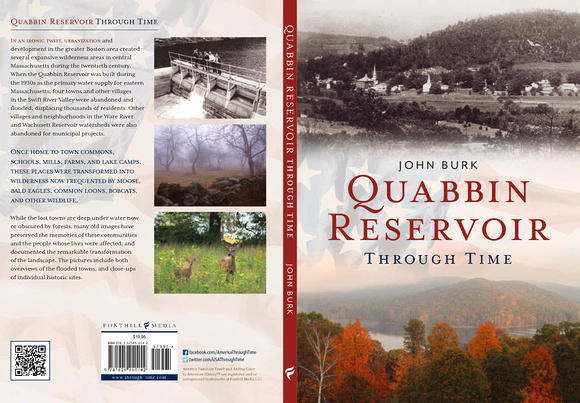

75 years ago, the landscape of the Swift River Valley in central Massachusetts was in the midst of a remarkable transformation as four towns were discontinued, abandoned, and largely flooded during the creation of Quabbin Reservoir, the water supply for eastern Massachusetts. Since that time, the reservoir has become an "accidental wilderness," a 40 square mile haven for wildlife in the midst of one of the country's most populous regions. In addition, thousands of acres of lesser-known watershed lands to the east, including the Ware River and Wachusett Reservoirs, were also taken during the 20th century.

I'm pleased to announce the recent release of Quabbin Reservoir Through Time:, a new book in Fonthill Media's America Through Time series. The book features 90 historic images paired with recent color photographs taken from the same vantage, along with an introductory history of the water supply projects.

Though nature has largely reclaimed most of the Swift, Ware, and Wachusett watersheds, many historic sites remain visible today. Arguably the finest outing for those with an interest in history is the former road to Dana Common (Gate 40) in Petersham, where an old town road leads past several old farm sites to the former site of Dana. Interpretive signs with pictures of the old buildings were recently posted at many of the old foundation sites, allowing visitors to compare past and present views.

For images of Quabbin Reservoir, the Swift and Ware Rivers, Wachusett Reservoir, and other nearby places, feel free to check out my central Massachusetts galleryL http://johnburk.zenfolio.com/p1068073715

With its variable topography and abundant precipitation, Massachusetts is home to a variety of distinctive waterfalls. Many of its largest cascades are found in the westernmost portion of the state in the Appalachian uplands of Berkshire County, while others are spread across the western and central foothills. Each of the seasons offering viewing potential. In spring, volumes are generally highest after winter snowmelt. Autumn brings colorful foliage and soaking rainstorms that recharge volume. In winter, unusual ice formations can change by the day. Below are some of my favorite and most photogenic waterfalls in the various regions. There are plenty of others well worth a visit - good luck exploring!

Tannery and Ross Brook Falls, Savoy Mountain State Forest: This hidden ravine in Savoy Mountain State Forest is a special treat for waterfall enthusiasts, as it is home to two large, distinct cascades within a few hundred feet of each other. The short trail follows Tannery Brook, then descends via a set of stairs to the base of the ravine. The first cascade on Tannery Brook is to the right of the steps, while the falls on Ross Brook is ahead to the left. If you have time for an additional hike, the Busby Trail offers an easy climb to the summit of Spruce Hill and one of the finest viewpoints in the Berkshires, including a great look at Mount Greylock across the valley. Directions: From Route 2 (Mohawk Trail) in Savoy, turn south on Black Brook Road for 1.4 miles, then right on Tannery Brook Road for 0.7 miles to parking area at Tannery Pond.

Rocky gorge and falls on Tannery Brook in early autumn.

Rocky gorge and falls on Tannery Brook in early autumn.

Campbell Falls, New Marlborough: These cascades in the southern Berkshires are one of the more remote attractions in Massachusetts, but it's well worth the effort and an easy walk once you get there. The Whiting River drops roughly 60 feet in several steps after funneling through a narrow gorge at the lip of the falls. Look for red columbine wildflowers during the spring. Directions: take Route 57 to New Marlborough, then follow New Marlborough-Southfield Road to Southfield, then left on Norfolk Road to Campbell Falls Road.

Late spring high water at Campbell Falls.

Late spring high water at Campbell Falls.

Bash Bish Falls, Mount Washington (town of, not the mountain): Bash Bish Falls has long been one of the signature attractions of the Berkshires. It is famous for its twin cascades, though one of these has been blocked in recent years by downed trees from a storm. Directions: From Routes 41 and 23 in South Egremont, bear left on Route 41, then right on Mt. Washington Road for 7.5 miles, right on Cross Road, right on West Street, left on Falls Road and continue 1.5 miles to main parking area.

Bash Bish Falls is one of Massachusetts' best-known natural features.

Bash Bish Falls is one of Massachusetts' best-known natural features.

Wahconah Falls, Dalton: This scenic cascade in the central Berkshires is one of the state's most accessible waterfalls, as it is reached by a very short walk from the trailhead. Wahconah Falls Brook drops 40 feet into a pool, passing some neat formations carved into the rocks by the flowing water. Directions: From Routes 9/8A in Dalton, drive 2.6 miles east of town center and turn south on North St./Wahconah Falls Road and follow signs to entrance.

Bear's Den, New Salem: En route to its confluence with Quabbin Reservoir, the Middle Branch of the Swift River, one of the reservoir's largest sources, carves a path through a neat falls and gorge near old mill sites. The falls are a short walk from Neilson Road; use caution around the rocks and ledges. From Route 202 north of New Salem center, turn west on Elm Street, then left on Neilson Road and continue to roadside parking area on right.

Swirling pools at the base of the Bear's Den falls.

Swirling pools at the base of the Bear's Den falls.

Royalston Falls, Royalston: The unrelenting carving power of even a small forest stream is evident along the valley of Falls Brook near the New Hampshire state line. From the Trustees of Reservations parking area adjacent to the Newton Cemetary, follow the combined Tully and Metacomet-Monadnock Trails on a moderate descent into the valley. After crossing the brook on a wood bridge, go right and follow the yellow-blazed Tully Trail for 0.3 miles to the falls and gorge. Nearby Doanes Falls, a quarter-mile long series of cascades on Doane Hill Road near the Tully Lake campground, is also well worth a stop in this area. Directions: From the junction of Routes 2 and 32 in Athol, follow Route 32 north past the junction with Route 68 in West Royalston, then continue 1.7 miles to the entrance on right.

The narrow cascades of Royalston Falls.

The narrow cascades of Royalston Falls.

Trap Falls, Willard Brook State Forest: Waterfalls are few and far between in eastern Massachusetts, thanks to the mostly level topography of the coastal plain. The distinctive triple cascades of Trap Falls are a highlight of the Willard Brook State Forest in Ashby, a short drive east from Mount Watatic. Directions: The parking area is on Route 119 in Ashby, a few hundred feet west of the Ashby-Townsend town line.

Amidst the bustle of metropolitan Boston, visitors in the spring are treated to beautiful floral displays as the city's parks and gardens come into bloom during April and May. Two especially colorful highlights of the 'Emerald Necklace,' a chain of parks that serve as welcome oases from development and traffic, are the Arnold Arboretum and the Public Garden. As recent springs such as the warm 2012 and cool, late 2013 have proven, flowering times can vary by several weeks - it's worth checking for updates before planning a visit.

Located in the Chestnut Hill neighborhood, the Arnold Arboretum is a treat to explore during the spring. Within its 265 acres are more than 15,000 trees, shrubs, and flowers from around the world. The Arboretum is managed by Harvard University, which uses the grounds for research and public education, and the city of Boston, which is responsible for security and infrastructure. Visitors enjoy walking on several miles of paved roads and footpaths that offer easy exploration of the grounds. You can do an short outing with family or just relax on the lawns, or a long circuit hike of several miles. My favorite walk, time permitting, is a 4.1-mile circuit from the visitor center that visits Peters and Bussey Hills.

Lilacs and early leafout at the Arnold Arboretum.

Lilacs and early leafout at the Arnold Arboretum.

One of the Arboretum's popular spring events is a festival during the peak of the lilac blooms in early May. The lilac gardens, which include roughly 200 varieties, are located along the base of Bussey Hill near the center of the property. The nearby Bradley Rosaceous Collection has many colorful plantings including roses and cherries. Another must-see is Peters Hill at the Arboretum's southern boundary. From the summit of this 240-foot eminence, you'll enjoy sweeping views over apple and cherry trees to the Boston skyline. For easy access, you can park on Bussey Street and enter at the Peters Hill or Poplar gates (be sure to check regulations when parking on any of the streets).

Visitors enjoy spring at the Public Garden.

Visitors enjoy spring at the Public Garden.

Once a salt marsh, the 24-acre Boston Public Garden was designed and established during the mid-19th century.The gardens are bounded on the south by Boylston Street, on the south by Arlington Street, and on the north by Beacon Street; Charles Street divides Boston Common from the gardens. The plantings include variety of both native and exotic trees, shrubs, and flowers. The latter are maintained throughout the growing season from stock at greenhouses at Franklin Park. A favorite for many visitors are the colorful tulips, which bloom in red, purple, yellow, and other hues in early spring. Visitors may also enjoy a swan boat tour on the pond, and views of ducks, swans, squirrels, songbirds, and other wildlife. In autumn, the trees offer foliage displays into November, long after color has faded from most other regions of New England.

For directions and more visitor information, visit the Arnold Arboretum's website http://www.arboretum.harvard.edu, and the City of Boston Public Garden page http://www.cityofboston.gov/parks/emerald/public_garden.asp

Exploring the White Mountains can seem daunting, as the region is home to New England's highest mountains and most rugged terrain, including nearly 50 peaks that exceed 4,000 feet. Fortunately, the region offers hundreds of miles worth of trails with a variety of options for hikers of all abilities, and a wealth of opportunities for photographers. Below are some recommended outings that offer great views of Mount Washington and the Presidential Range.

1. Mount Sugarloaf. This little mountain offers some of the finest views in New England per amount of effort. From the trailhead on Zealand Notch Road, the trail follows the river, then makes an easy climb past some giant glacial boulders. After a brief steep section, it reaches a notch between the north and middle summits. From here the trail to the right offers a short 0.3-mile climb to the north summit, where there are excellent views of Mount Washington, the Presidential Range, and the surrounding area. The route to the middle summit is slightly more rugged and requires a quick climb up a ladder. Though Zealand Notch Road is closed to traffic in winter, hikers can park at the nearby pullout on Route 302 and walk up the road to the trailhead.

Late winter view of Mount Washington and the Presidential Range from North Sugarloaf.

Late winter view of Mount Washington and the Presidential Range from North Sugarloaf.

2. Square Ledge. This massive rock outcropping is located on the slopes of Wildcat Mountain across from the AMC Pinkham Notch Visitor Center and offers a fine view of Mount Washington's east face. The trail begins opposite the visitor center on the east side of Route 16 and offers an easy to moderate 0.5-mile climb that gains 500 feet.

3. Lowe's Bald Spot. This longer outing along Mount Washington's lower east slopes leads to a rocky, partially open shoulder with excellent panoramic views of Mounts Adams and Madison, Boott Spur, the Lion's Head, and the valley to the north. The elevation gain is 850 feet. This trail also begins at the AMC visitor center and climbs gradually for 1.9 miles to cross the Mount Washington Auto Road near the 2 mile marker. It then follows the Madison Gulf Trail for 0.2 miles to a side trail that offers a quick climb to the outcropping and viewpoints. Backtrack for a 4.4-mile round trip.

A treeline view of Mounts Eisenhower and Washington from Mount Pierce.

A treeline view of Mounts Eisenhower and Washington from Mount Pierce.

4. Crawford Path to Mount Pierce. It may seem odd to include a 4312-foot peak of the Presidential Range in a list of easy hikes, but the historic Crawford Path, which was originally a bridle path, offers a moderate, well-graded climb along the southern Presidentials with no steep sections. From the area around Mount Pierce's summit there are outstanding views of Mount Washington and much of the Presidential Range, including Mount Eisenhower. From parking areas off of Route 302 in Crawford Notch near the AMC Highland Center, the Crawford Path leads past Gibbs Falls after roughly 0.5 miles and Mizpah Cutoff at 1.9 miles, then emerges from the trees below the summit, which it reaches at 3.2 miles.

Good luck exploring, and for more images and ideas feel free to visit the New Hampshire gallery: http://johnburk.zenfolio.com/p701332216

An exciting astronomical event of recent has been the visibility of a comet called PANSTARRS. Officially known as 'c/2011L4,' it was discovered in June 2011 and is one of several comets that will be visible in the night sky during 2013.

During March 2013 PANSTARRS has been visible on the western horizon (270 degrees) after sunset. In an unusual twist, photography may be the best means of viewing this faint comet. Because of the glare of twilight, it is often difficult or impossible to see with the naked eye or even good binoculars. However, it often will be visible on long camera exposures. On the 13th and 14th, the low crescent moon has served as a useful reference point.

This image was taken from a vantage in Harvard, Massachusetts, looking due west to Wachusett Mountain. The row of lights is from the mountain ski area. This image was taken roughly 45 minutes after sunset. At the time the comet was not visible to the naked eye, but was through binoculars. It vanished into oncoming low clouds and light pollution on the horizon shortly thereafter. Note the tail, which is visible even in this distant view.

For more information about viewing later this month, there are several good sources on the Web including http://earthsky.org/space/comet-panstarrs-possibly-visible-to-eye-in-march-2013. Another, brighter comet known as 'ISON' will be visible in late 2013.

On a recent trip to the Maine coast I caught the famous Nubble Lighthouse as a powerful coastal storm cleared southern Maine at sunset. The wild evening including a double rainbow, crashing surf, and sustained fierce wind - in fact gusts of more than 70 miles per hour were recorded by the National Weather Service.

The 'Nubble' draws its name from the tiny island it sits atop, which is a short distance offshore from the mainland coast near York Beach. It owes its popularity to easily accessible views from Sohier Park, a waterfront park that encompasses the slab of rocky shore at the tip of Cape Neddick, and its proximity to the York beaches. Photographers and artists enjoy a variety of lighting conditions throughout the day, from spectacular sunrises in the morning to golden evening backlighting.

Though Nubble Island was visited by explorer Bartholomew Gosnold as early as 1602, in spite of pleas from many mariners to mark a safe passage along these rocky shores, the lighthouse wasn’t authorized until 1876. The 41-foot tower began operations three years later bearing a dark red coat of paint. It was repainted in its familiar white in 1902, the same year the photogenic red oil shack was erected near the lighthouse. After more than a century’s worth of management by keepers, some of who kept farm animals on the island, the light was automated in 1987.

The Nubble Lighthouse had a most unusual distinction in 1977 when it was included in a series of photographs and artifacts that were loaded the Voyager II rocket during its mission to photograph the solar system. These items, which also depicted landmarks such as the Great Wall of China were to educate potential extraterrestrials about Earth. In some winters, migrating snowy owls may take up residence on the island – watch for them perched on the lighthouse buildings and on the telephone poles.

The reward for braving the elements included the rainbow, shown below. It's always great to find unusual conditions at familiar viewpoints!

Although there are a few clusters of autumn color remaining as of mid-November, the 2012 foliage season essentially came to a close after Hurricane Sandy passed close by the region at the end of October. As detailed in the previous entry, the season started off very promisingly with lots of vivid red maple colors, but stalled significantly after a long stretch of bad weather. However, there were some nice color spots once the late species such as oaks and beeches turned in southern New England, including this vista above Quabbin Reservoir.

Below is a recap I did for Northern Woodlands magazine specific to New Hampshire and Vermont:

http://northernwoodlands.org/outside_story/article/northern-woodlands-foliage-2012-recap

It follows up a piece on 2011's unusual foliage and weather:http://northernwoodlands.org/articles/article/last-falls-foliage

Every season has a difference progression and, though it can be frustrating in the short-term when colors go bad, after the season it's interesting to see how it all relates.

While misty and rainy days make for ideal conditions for photographing subjects such as Kent Falls in Connecticut (above), there's occasionally the risk that moisture in the form of rain or high humidity can affect your camera. It's certainly frustrating when a body goes completely dead , but fortunately in many instances it will come back to life after the problem clears up, especially if the water contact was fairly light (as opposed to a full dunking or salt water, which are more likely to create big problems). The following are steps I've found helpful in dealing with these issues.

1. As soon as there's any evidence of moisture inside the camera (even if it is working correctly), try to keep it in the same position without turning it in different directions. This may keep water from reaching and affecting additional circuits and corners inside the body. As tempting as it may be to check, DO NOT turn on the power on until you're sure the camera is thoroughly dry, as this may cause an electronic short.

2. Though some suggest leaving external pieces attached, I immediately remove the lens, battery, and memory card, which protects them from being potentially damaged or compromised by the problem and also help the moisture dissipate from the body.

3. Now you have several options for the drying process. One possibility, especially if the water contact was light, is to place the camera in close proximity to an active light blub. The heat can slowly draw moisture out through openings such as switches and buttons. It should be close enough to feel the heat, but far enough away to not be in direct contact or feel hot to the touch.

Another simple and inexpensive option that has worked for many with wet cameras, lenses, and cell phones is to place the item in a sealed plastic bag with uncooked rice, which is excellent for absorbing moisture. You'll want to be careful that the grains and dust don't get into openings. Silica gel packs (which often come with electronic equipment and are definitely worth saving) are similarly effective.

4. Have patience. Problems may clear up in a matter of minutes or hours, or they may last as long as several weeks. Even if it looks like the problem has cleared up, it's best to continue the drying process for at least a couple days or longer. Continue to keep the camera/lens in a cool, dry environment. Try starting it with different combinations (i.e. lens or memory card attached, not attached, etc.) especially if there are symptoms such as beeps from the memory card door or unusual lens. Recently I had a Canon T1i out of service for an entire month, then suddenly come back to life.

5. Be aware that the camera may not function normally or consistently after a moisture incident - in other words be sure to take a bunch of test images and have a backup handy before heading out in the field again.

Over the next few weeks I'll post periodic updates from travels around New England (and possibly a diversion to the Adirondacks). These will be informal, and for more detailed reports feel free to visit photographer friends Jeff Folger's foliage page http://jeff-foliage.com and Jim Salge's blog for Yankee Magazine http://blogs.yankeemagazine.com/new-england-foliage/.

So far, signs point to an earlier autumn than in recent years, especially 2011. Early color has been steadily progressing in the hills of central Massachusetts and southern New Hampshire's Monadnock region. While most areas of New England are still a bit early for a trip with overall dynamic color, those planning road trips to 'seek the peak' should anticipate going sooner rather than later as October progresses.

One interesting exception has been the red, or 'swamp' maples in wetlands. These often turn quite early, sometimes in August, but have been fairly slow so far in 2012. However, a number of wetlands have colored up nicely in recent days. I've seen some very colorful swamps or watersides near the Quabbin Reservoir in north-central Massachusetts, and the Wapack Mountains, Mount Monadnock, and Gap Mountain in southern New Hampshire. If you were to concentrate on these wetlands, I'd say the upcoming few days would be worth a road trip. This image was taken on Monday, Sept. 24.

While foliage may not be peak in most areas yet, you can enhance images with even a trace of color by photographing in prime conditions, which include early or late day light and fog (and sometimes both). These may entail an early start or late evening, but it's well worth it when things come together. This image was taken on the Millers River in central Massachusetts - though it's still early in the region, the single maple above the bridge shows the changing seasons and the onset of foliage.

Good luck and happy searching!

New England's lighthouses offer visitors a variety of viewing options - many are easily accessible by car, while others are only visible via a boat (or airplane) tour or walking or hiking. Here are three favorite lighthouse hikes on Cape Cod that run the full gamut of length and time. While elevation gain is obviously minimal along the beaches, soft sand and exposure to sun and wind are potential hazards - be sure to bring plenty of water and sunscreen. Seasonal beach fees may apply, and all visitors should respect private residences.

Above: The trails to Race Point Lighthouse offer fine views across the tip of Cape Cod and the National Seashore.

1. Sandy Neck, Barnstable. With a round-trip of more than 12 miles, this outing is for the hardy only! From the trailhead at the ranger station, the Marsh Trail offers fine coastal habitat views of marshes, dunes, and woodlands as it passes four 'crossover' paths to the beach (which offer options for shorter hikes) before reaching the lighthouse and private residences at 6.5 miles. Many people return via the beach for a long loop.

To reach the trailhead, from Route 6 take Exit 5 and follow Route 149 to Route 6A. Turn left on 6A, then right on Sandy Neck Road after the sign for Sandwich. The parking area for the trails is to the left of the ranger station; trailhead to the right.

2. Stage Harbor and Chatham Lighthouses, Chatham. This much easier walk begins at Hardings Beach at the 'elbow' of Cape Cod in Chatham. From the entrance, walk to the left (east) along the beach for slightly more than a mile to the Stage Harbor Lighthouse, which marks the west side of a channel to Chatham's Stage Harbor. Look for the Chatham Lighthouse in the distance on the bluffs above the opposite side of the harbor.

To reach Hardings Beach, from Route 28 in West Chatham, turn south on Barn Hill Road for 0.4 miles, then right on Hardings Beach Road for 0.8 miles to the parking area.

3. Race Point Lighthouse, Provincetown. The Race Point Lighthouse is one of three beacons on the outer lands of the Cape Cod National Seashore's Province Lands dunes. From the Race Point Beach entrance, it's roughly a 45-minute walk south along the very tip of the Cape to the lighthouse. It can also be reached by via a fire road off of the road to Herring Cove Beach (the trailhead is marked with a sign for Hatch's Harbor). This route is on mostly packed ground and offers nice marsh views. The nearby Wood End and Long Point Lighthouses are also accessible by walks that cross the breakwater in Provincetown; be sure to have maps and tide info and allow plenty of time.

To reach the Province Lands, follow Route 6 all the way to Provincetown, then turn right at a traffic light at a sign for the national seashore and follow signs for Race Point (maps and information are available at the National Seashore visitor center).

This third installment of the Western Massachusetts foliage planner (split off of #2 to provide more details) features the uplands east of the Connecticut Valley. These hills and valleys are similar to the western area of the state in their subject matter, but also boast some large lakes and conservation areas that are part of the Massachusetts water supply system.

This region has many small towns and villages with classic commons and greens, such as New Salem (above). Others well worth a stop include Petersham, Royalston, Barre, West Brookfield, Hardwick, and Oakham. If you like pastoral scenes, Hardwick, New Braintree, North Brookfield and other towns have a lot of agricultural land with long views.

The dominant physical feature of this region is Quabbin Reservoir, a 40-square mile reservation created as a water supply for Boston. Some of the best and most easily accessible views are at Quabbin Park off of Route 9 in Ware and Belchertown, which includes a paved auto road. The Enfield Lookout has spectacular views up the valley to Mount Monadnock in New Hampshire. There are more than 50 other access areas that are open to hiking (biking is allowed in some areas).

Route 122, which was recently dedicated as the 'Lost Villages Scenic Byway,' follows the northern boundary of the reservoir, then continues past other conservation areas and town centers in New Salem, Petersham, Barre, Rutland, Oakham, and Paxton. There are some nice wetland views that are especially colorful in early autumn when the red maples are turning. For the best views, be sure to get out and explore the many trails along the route. Route 62 from Barre east has some nice country views as well.

Expect a full range of weather possibilities here - this unusual autumn snowstorm at Quabbin Reservoir was an abrupt interuption from a period of record warmth!

If you're up for a relatively easy climb, there are excellent views along the New England National Scenic Trail from Brush Mountain in Northfield, Mount Grace in Warwick, and the Erving Ledges above the Millers River. The nearby Tully Valley watershed has a number of conservation areas with vistas on Tully Mountain in Orange and Jacobs Hill in Royalston. Tully Lake offers the possibility for dramatic foggy scenes.

The highest mountain is 2006-foot Wachusett Mountain near Princeton, which has an auto road and hiking trail network. There are long 360-degree views from the summit. To the north, Mount Watatic in Ashburnham requires a rugged short hike but has some outstanding views. Another great vista is at Crow Hill at Leominster State Forest, reached by a half-hour hike that traverses a dramatic sheer cliff. All of these are part of the Midstate Trail.

These are just some of the possibilities to get your trip started -- feel free to browse the site for more ideas. Again, Columbus Day weekend is generally a good time in this region, though in years like 2011 it was still early and there was plenty of green. I'd also suggest a mid to late September visit, when the red maples are at peak, and you'll often find late oak and beech color towards the end of October.

Good Luck!

In Part 1 on Western Massachusetts foliage viewing I gave a quick overview of the region.Now, here are some specific recommendations (this is in progress and will be updated shortly!)

In the Berkshires, the Mount Greylock State Reservation includes a 16-mile byway that visits the summit of southern New England's highest mountain. There are a number of roadside vistas near and at the summit, and while driving up you can really see the different colors at different elevations. In addition to the summit, there are many short trails that lead to other features - I strongly recommend Rounds Rock Trail, Robinson's Point, and March Cataract Falls if its been raining.

The Savoy Mountain State Forest off of the Mohawk Trail Highway has an easy trail to Spruce Hill, where there's a great panorama of Mount Greylock and the Berkshires and southern Green Mountains, and also two large waterfalls in one ravine.

Pittsfield State Forest has an auto road to the summit of Berry Mountain, where there's a high-elevation pond and westerly views, also some nice streams and cascades near the campgrounds and day use areas.

Mount Everett State Reservation has views across the southern Berkshires and another high-elevation pond, as well as the cascades of Race Brook Falls.

The Mohawk Trail Highway is a well-known touring route. It follows Route 2 from Athol west to Mount Greylock near Williamstown, Some of the most dramatic scenery is in the Cold River Valley, a narrow corridor with steep slopes. The road then climbs the Hoosac Range to a series of overlooks. If you have time, make a detour on River Road in Charlemont, which winds along the dramatic Deerfield River valley to Vermont.

The lesser-known Jacobs Ladder Trail (Route 20 area) follows the watershed of the Westfield River, a designated National Wild and Scenic River.

In the Connecticut Valley, one of the best vistas is from Mount Sugarloaf, a great panorama of the valley and the village of Sunderland. There's an auto road and several short hiking trails with brief steep climbs.

Mount Holyoke has another fine summit view that can be reached by car or on foot, and there are some nice farm field views at its base as well.

The French King Bridge (above) is a popular spot on the Mohawk Trail with dramatic views of the French King Gorge and the Connecticut River. You can take a boat tour of the gorge run by the Northfield Mountain Recreation Center.

The next installment will have details on central Massachusetts, the area east of the Connecticut Valley.

With leaves having only recently emerged on the trees, it may seem a bit early to be thinking of fall foliage, and many of us are certainly in no hurry to think beyond the warm weather. However, since many people make travel plans in advance and I often get asked about viewing routes and trails, here are some thoughts and recommendations.

For a (mercifully) quick geography primer, the area west of the Connecticut Valley, especially Berkshire County, is comprised of the Appalachian Mountains and their foothills. The higher summits, which are basically southerly extensions of the Green and Taconic Mountains of Vermont, range in elevation from 2000 to 3500 feet, capped by Mount Greylock in the state's northwest corner. The Connecticut River Valley has a much lower elevation, but is home to a number of low mountains, hills, and ridges which were formed by ancient volcanoes. Although these peaks are low in statue - just a few hundred feet in some instances - don't let the numbers fool you, as they have outstanding panoramic views. To the east, the center of the state has many rolling hills and wetlands, with a few isolated higher mountains of 1500-2000 feet. The view below is from Mount Sugarloaf in South Deerfield, at an elevation of only 650 feet!

How does this relate to foliage viewing? There are subtle differences in the forest types - the colorful northern hardwoods such as maples, birches, and beeches are common at the higher elevations, which oaks are predominant lower. The peak foliage viewing correspondingly occurs earlier at the higher elevations to the west, and later in the valleys. If you miss great color in the Berkshires, head to the valleys, and if it's mostly green in the valleys, head for the mountains.

Defining the 'peak' can be a bit tricky, especially with some of the unusual autumns we've been having recently -- 2011 was a prime example. Columbus Day weekend is traditionally cited as an optimal time, but you will often find the best color in the Connecticut, Millers, and Quabbin Valleys later in October, and some pockets of oak and beech foliage may be visible into November. It's best to follow updates and the weather during a given year - pay attention to those cold and frosty nights, as they trigger leaf color changes.

For photographers, the region has a nice diversity of subject matter. There are mountaintop and hill views, rivers, wetlands, small towns with historic commons and churches, a handful of historic covered bridges, and scenic valley farms with pumpkin patches and roadside stands. There are a full range of driving, hiking, and other recreational options, and many nature preserves and state forests.

In the next installment I'll share some suggested routes and destinations.

At first, rainy or misty days might not seem like the best time for outdoor photography. However, those willing to brave the elements are rewarded with outstanding lighting conditions for a variety of subjects and opportunities for magical 'Smoky Mountain' scenes.

One advantage overcast days have over sunny days is diffused, even light, with nicely saturated colors and shadows eliminated. These are ideal for waterfalls, cascading streams, forest scenes, gorges, and wildflowers. - in fact, many of these are nearly impossible to get a good photograph of if it's bright out. Raindrops and dewdrops can greatly enhance photos of flowers and leaves. Unless fog or low clouds enhance your image, be sure to crop the white sky out of your image, otherwise it will show up as a colorless highlight. You'll want to use a tripod whenever possible, as shutter speeds are likely to be pretty low, and long exposures make for neat flowing water shots.

Spring is a great time for this sort of photography, as rivers, streams and waterfall have volume, wildflowers are up, and forests have fresh new leaves. And of course autumn in New England offers a full range of colors

This photograph of a cascading stream on the Appalachian Trail was taken near the base of Bromley Mountain in the southern Green Mountains of Vermont. The soft, low light allowed for a long exposure and rich color on the newly emerged leaves.

Unusual weather has been the norm over the past year, and the effects of the recent summery temperatures are apparent even on the ridge of the Presidential Range and Mount Washington in New Hampshire's White Mountains, where considerable snowmelt looks well out of place for March. Last weekend, the "snow bowl" of Tuckerman's Ravine was active with skiiers and snowboarders, who enjoyed record-breaking warmth while braving the steep slopes of the headwall. In fact, the waterfall atop the headwall was open and flowing, weeks ahead of schedule.

The ravine, which is a cirque carved by alpine glaciers below Mount Washington's summit, can receive as much as 55 feet of snow in one winter. The first known skiier was in 1914, and during the 1930s it hosted a variety of events including giant slalom races, Olympic tryouts, and three summit-to-base races known as the 'American Infernoes.' Today, it is a very popular destination for winter recreation, especially in late winter and spring - the season can continue as late as June.

The base of the ravine is reached by a 2.4-mile hike that gains roughly 1850 feet from the trailhead at the Appalachian Mountain Club Pinkham Notch visitor center on Route 16 between North Conway and Gorham. While the climb is almost constantly moderate, there are no real steep sections, and the footing is usually good on the well-packed trail. It's a fine winter hike for those who wish to explore an interesting area of Mount Washington without going all the way to the steep, exposed summit, though all visitors should check signs and advisories regarding avalanches - some trails and places such as the 'Lunch Rocks' may be dangerous.

(UPDATE ADDED 4/4: Sadly, shortly after this was published, there was another fatality involving a hiker from Massachusetts who fell down an icy slope of the ravine after climbing to the summit, as detailed here: http://www.unionleader.com/article/20120110/NEWS07/120119994&source=RSS

In this image a snowboarder passes by the right of the open waterfall on March 18, 2012, on a day the summit broke the previous high temperature by more than 10 degrees! More pictures may be viewed here: http://johnburk.zenfolio.com/?q=%22mount%20washington%22

As many fellow photographers and hikers know all too well, thanks to a variety of unusual weather and climate events, the 2011 foliage season was unusual, and in many areas rather drab and/or short-lived. For an upcoming autumn issue of Northern Woodlands magazine, I'm putting together a text/photo article that details the relationship between climate and foliage on both short and long-term intervals, in the process addressing the anthracnose that affected sugar maples and other hardwoods, salt spray from Hurricane Irene, and the unusually mid autumn and how it reflects a long-term trend. Call it making the best of an often bad situation! The photo below shows late foliage at Quabbin Reservoir after the first of two unusual October snowstorms.

I'm pleased to provide a number of images for a newly released report on conservation and New England forests related to work done by Harvard Forest, Highstead Arboretum, and the Wildlands and Woodlands project. Check out the report and related information here:

Hello Everyone,

Thank you for visiting the new site. This is a test of sorts of the new blog feature.

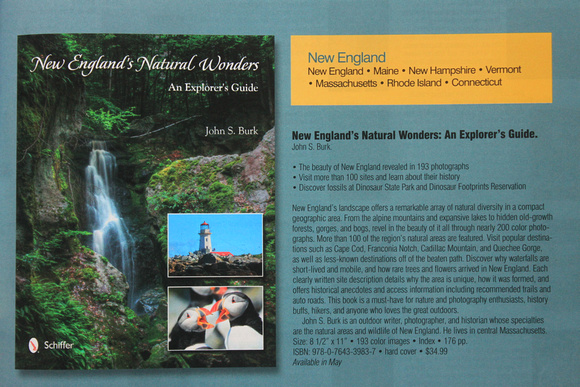

Here's the catalog copy for a new book that should be out in May, New England's Natural Wonders: An Explorer's Guide. It details the various unique and diverse natural features of New England, including alpine mountains, monadnocks, bogs, gorges, waterfalls, coastal areas, dinosaur track sites, and the like. It includes nearly 200 color photographs and recommended trails, driving directions, and historical notes. The cover features Royalston Falls near my home in the North Quabbin region of central Massachusetts. Thanks to the folks at Schiffer Publishing and family, friends and collegues for encouragement and being great resources.

For more info, including signed copies, feel free to email me at [email protected]